A while ago during lockdown, the Cumbria Wildlife Trust organized an online session on bird recognition which turned out to be one of the most entertaining wildlife presentations I’ve taken part in. This included beginner’s tips on recognising bird song and now whenever I hear calls of ‘tea-cher tea-cher’ in a wood or chants of ‘I don’t like football’ I know that there is probably a great tit or wood pigeon around.

However, memory aides are just one way to recognise bird song and smartphone apps provide another option too. This led us to try one of the best known examples, called BirdNET, and on countryside walks I quickly became used to hearing an urgent, ‘shhh, keep still’ when recording was underway. This added a whole new dimension to nature watching as did a friend introducing us to an app called Seek for identifying wildflowers and garden plants.

For some birds, an app isn’t really needed, such as for the curlew with its distinctive downward curved beak and burbling ‘cur-lew’ call

For a while I’ve been meaning to dig into how these types of apps work and, from what I’d already read, I expected machine learning and artificial intelligence to play a large part and citizen science/crowdsourcing too, but wasn’t quite sure how it all fitted together.

Starting with bird song first, the three main ingredients are usually a database of digital recordings, a way of recording sound (typically your smartphone), and software to compare the new and stored recordings.

With BirdNET, the recorded sound is transformed into a spectrogram, which is a visual representation of the bird’s call with frequency on the vertical axis, time horizontally, and the brightness indicating the amplitude. After highlighting the part of the graph that you’re interested in, the resulting snippet is sent off for analysis, with an almost instant assessment that takes account of your location and the time of year. For the technically minded, the analyses are performed using a deep convolutional neural network approach.

The app was developed by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology as part of a long term research program into the automated analysis of bird song, in collaboration with Chemnitz University of Technology in Germany.

Perhaps surprisingly, the lab is also home to another widely regarded app, called Merlin Bird ID. However, its roots are different as it started out as a digital field guide with structured questions to help identify the bird type from its size, colour and behaviour. A SoundID function was only added some time later and from a quick look online this seems to use a similar (but not identical) database and machine learning approach to BirdNET. However, rather than requiring a live connection, instead you download a so-called ‘Bird Pack’ for your region with a vast amount of information to explore offline.

Merlin also has a PhotoID function, but if you’ve ever tried taking photos of woodland birds with a smartphone, you may wonder how useful that is. Enthusiasts suggest that one way to get better results is to use a camera and zoom lens for the initial image, and then take a photo of the camera’s display screen with your phone.

Both of these apps give outputs in probabilistic terms rather than as a definitive result, starting with the most likely answer first. You therefore need to use your own experience and judgement to decide if the answers are correct, in part based on the additional information on bird behaviour you can find by clicking on the images provided.

Most bird recognition apps work in this way and acknowledging the uncertainty is even more important in plant recognition, where you really need to take the results with a pinch of salt. For example, you’d be strongly advised not to go foraging for a mushroom feast with an app or to pull up native wildflowers in the garden just because it claims they are a weed!

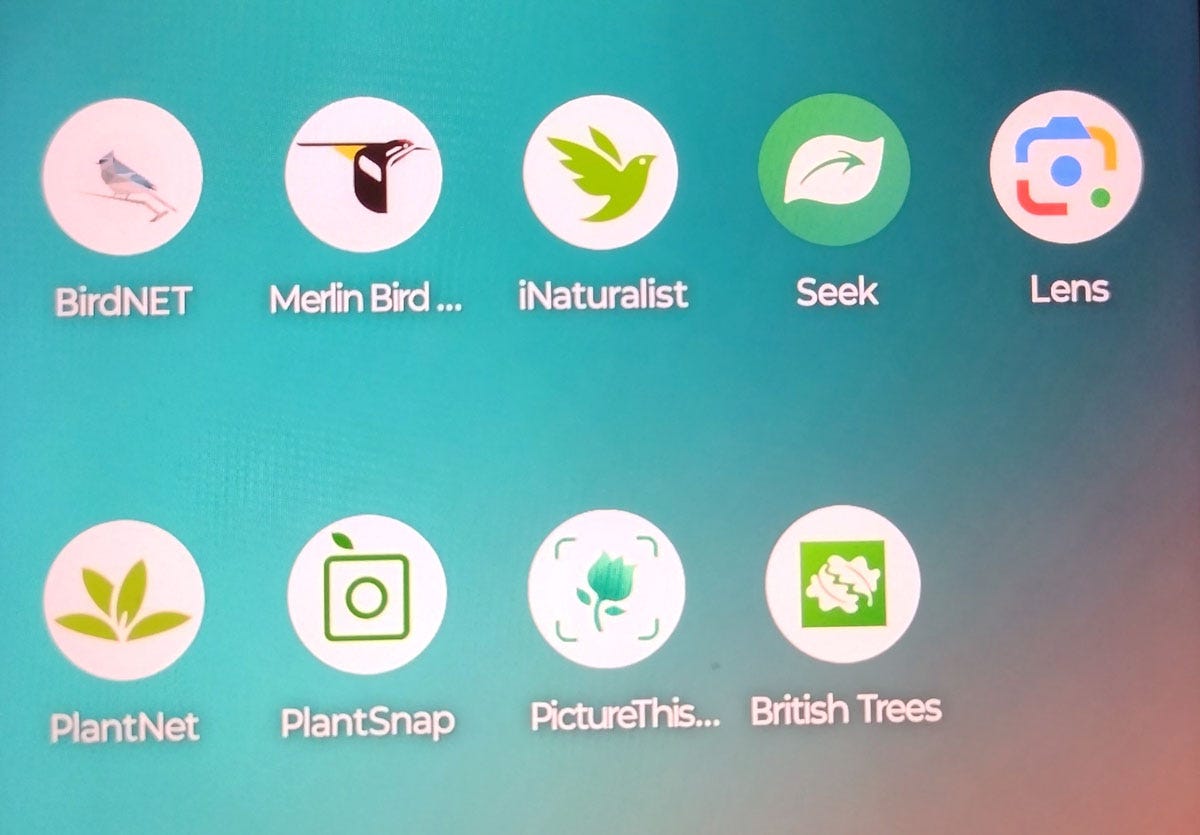

Some of the apps mentioned in this post

Three of the best known are PlantSnap, Pl@ntNet and PictureThis, and all have slightly different audiences. The first, PlantSnap, is firmly in the business of providing a rapid answer using artificial intelligence, which can be done on-the-fly without taking a photo if you wish, using so-called augmented reality.

In contrast, Pl@ntNet uses a more detailed approach, building up a profile of the plant from photographs of its leaves, fruits, flowers and bark as appropriate. It has been developed by a consortium of French organizations and in addition to being popular with enthusiasts is designed to support professional users, such as foresters, farmers and customs officers.

The third, PictureThis, is billed as the ‘botanist in your pocket’ and is particularly aimed at gardeners as it also diagnoses health problems for plants and suggests solutions, such as whether a plant needs watering.

The Seek app identifies birds, insects and mammals too, and was developed as part of the iNaturalist initiative, which was started by the National Geographical Society in the USA and the California Academy of Sciences. As the website says, ‘iNaturalist is an online social network of people sharing biodiversity information to help each other learn about nature.’ Nowadays research and conservation organisations from more than 20 countries participate and iNaturalist’s own app provides a way for experts and enthusiasts to submit and share information.

For Android users, Google Lens is another possibility and can be used for pretty much any subject; for example, in a Belgian bar earlier this year, I was genuinely surprised that I could take a photo of a notice board and get an immediate English translation for what was on the menu! The iOS (iPhone) equivalent is Visual Look Up.

There are of course many other examples both free and paid, with some paid apps offering a free trial period, such as PlantSnap and PictureThis. Other well-regarded apps include Birda and the digital field guide from the Woodland Trust (called Tree ID or British Trees).

Some more general considerations are whether a wireless connection is required when you are out and about, the credentials of the developers (botanists, bird experts etc.), and how comprehensive the database is for your part of the world. A crowdsourcing element might also appeal by allowing you to swap ideas with other enthusiasts and for your sightings to be used in plant and wildlife conservation efforts.

It’s also worth checking the extent to which your information is shared and some such as iNaturalist give the option of generalising your location to a few hundred square kilometres, rather than giving the exact coordinates of where you live, for example!

You can also find comparison tests online but it’s worth double checking the publication date as this is a rapidly developing field and the capabilities of apps tend to leapfrog each other as more is learned.

Acknowledgements

With thanks to the website descriptions for these various apps and to the Nature Notice Board whose post on nature apps earlier this year helped to spark the idea for this post.

Google lens identified the bizarre parasitic toothwort quicker than our trail mate the professional botanist did. And presumably will only get better. (The app not the botanist)

I like PlantNet. It uses the data to refine records of plant distribution. And as far as I can tell it’s very accurate.

I’ll check out your bird song recommendations.