In hydrometeorology - as in many other walks of life - the idea of getting something for nothing is appealing, although the reality is usually more complicated than that.

Opportunistic sensing is one example - typically using smartphones and/or communication links for another purpose - with an increasing number of applications in environmental monitoring.

A recent post on rainfall monitoring (see later) reminded me of that and got me wondering whether that term could also be applied to flood monitoring – a related area where collecting sufficient data can be a huge challenge.

Traditionally, meteorologists use an array of observation systems to help understand what is going on in the atmosphere, such as satellites, automatic weather stations, weather radar, wind profilers and weather balloons.

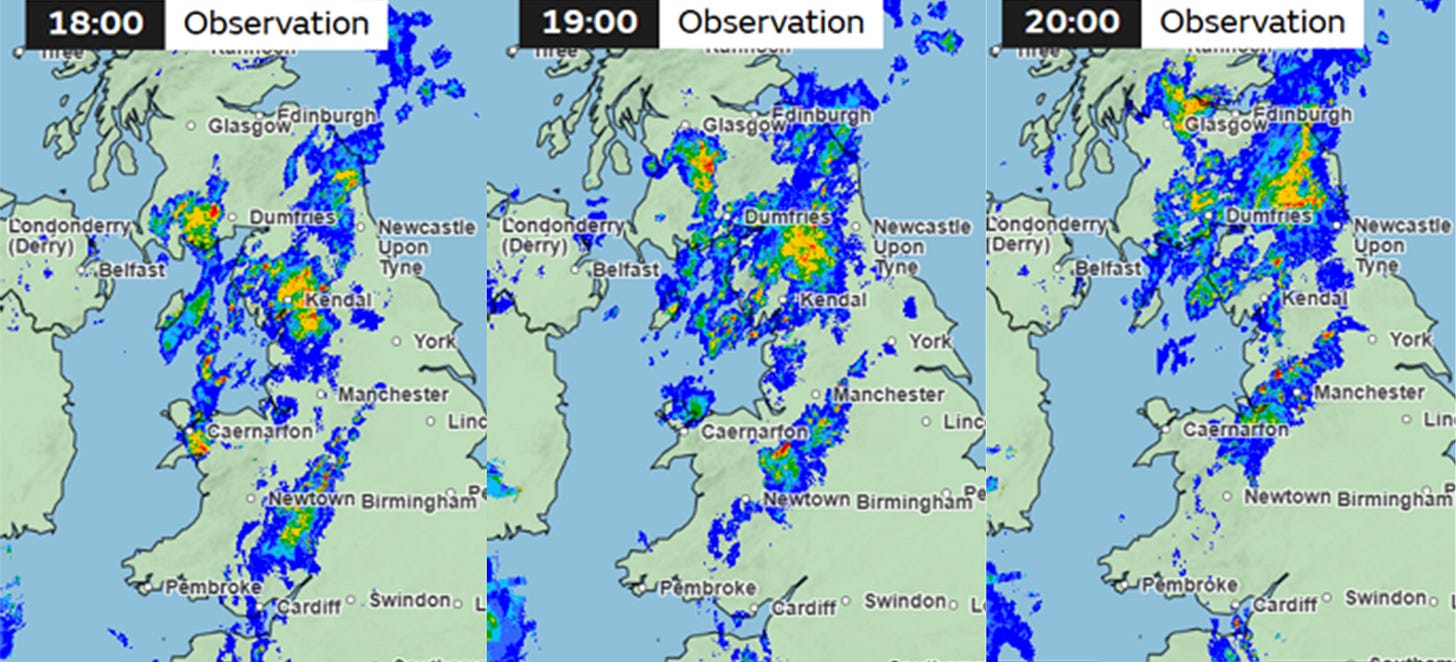

Weather radar images of heavy rainfall heading through the UK last weekend (images credit: Met Office)

However, as numerical weather prediction models improve, more data is always desirable, particularly for fast developing, localised events such as flash floods and floods in urban areas.

In meteorology, one of the earliest opportunistic examples was when airliners were added to the mix, using existing aircraft sensors and communication links to collect a range of parameters, such as air temperatures, and infer more, such as wind speed and direction. It’s interesting to think that when you fly off on holiday your trip may be making a small but meaningful contribution to that day’s weather forecasts! Partner airlines include British Airways, Easyjet and the main US carriers.

Illustration of information flow in the international Aircraft Meteorological Data Relay (AMDAR) observing system, initiated by WMO more than thirty years ago in partnership with airlines and national meteorological services (www.wmo.int)

More recently, researchers have started looking into the practicalities of gathering air temperatures from road vehicles, and possibly rainfall durations and intensities too based on windscreen wiper speeds, so maybe one day your car could double up as a mobile weather station (voluntarily of course)?

There’s no shortage of other ideas, such as the use of personal weather station data in operational weather forecasting models - gradually becoming a reality - and using smartphones to estimate air temperatures, atmospheric pressure and solar radiation, based on the existing sensors that many phones have for battery condition, barometric pressure and ambient light.

Indeed, one of the interesting things in science is watching how ideas grow from small beginnings into useful operational techniques (or, in the jargon, from research to operations). That post I mentioned earlier - by Weather with a Twist - describes one that may be nearing maturity, namely estimating rainfall from the tower-to-tower microwave link signals used by cellphone operators. A decade or more isn’t unusual for ideas to come to fruition; for example, in the first edition of ‘Hydrometeorology: Forecasting and Applications’ I included just a single sentence on that topic, but now nearly fifteen years later the latest edition has half a page.

Many of these techniques are potentially also useful in flood warning and forecasting. However, if you also count one-off measurements as opportunistic then one well known approach - the humble bucket survey - has been around a long time. Here, the idea is to look for evidence of rainfall amounts after a flood from any suitable receptacles lying around, such as water troughs and upturned cans and buckets (hence the name). Of course, it’s never clear how much water was already in there beforehand, but this at least gives an idea.

For flood modelling, after a major event it’s also important to know the highest water levels reached and survey teams are often sent out at short notice to record elevations, based on high water marks on buildings, debris on roads and river banks and other clues. On a riverside walk, if you’ve ever wondered why some trees are festooned with plastic bags, a recent flood might be the culprit.

In some places, historic floods are recorded for posterity as in these signs/markers seen in (left) Kendal before the Storm Desmond floods in 2015 and (right) in Mozambique after the 2000 floods

However, peak flows are the real prize and in more remote areas hydrometric teams would once camp out for weeks at a time to measure high flows as they occurred. This approach laid the foundations for water resources assessments in some parts of Africa, for example.

The modern day equivalent is to be prepared to go out at a moment’s notice and in Somalia I well remember a trip on which we abandoned plans for a day in the office to catch the peak of a flood as it passed along a major river.

Checking in for our mess accommodation near the gauging station in Somalia

Heading out from Mogadishu, the paved road soon turned to dirt and after several hours along bumpy tracks, sandy hills gave way to expansive views toward the arid Ogaden region in Ethiopia. Before dark we had just enough time to make a single flow measurement and then spent another couple of hours the following morning before heading back - all that effort for just two points on a graph, but important nonetheless in helping to establish the level-flow (stage-discharge) relationship for the site.

Much more recently, when out for a walk in the Scottish highlands, I had a chance meeting with a SEPA river monitoring team, one of whom turned out to have made the highest flow measurement ever recorded in Scotland, and possibly the UK. With hindsight I should have shaken his hand as at more than 1400 cumecs1 it beat our 900-1000 cumecs from Somalia by some margin!

So, here’s to the power of lateral thinking and it’s worth reflecting that some of this would have seemed like science fiction just 10-20 years ago.

1 cumecs is shorthand for cubic metres per second

Further reading

Nuking the rain: using cellphone towers to measure rainfall, Aaron Price, Weather with a Twist, 25 August 2024

Hydrometeorology: Forecasting and Applications, 3rd edition, Kevin Sene, 2024, Springer Nature, Cham, Switzerland, 516pp.

What Scottish river was that? (Spey would be my guess)

Great stuff.

Do I get a bonus point for recognising the Kendal flood marker?